Breathing Gas Monitoring Devices

A submersible Pressure Gauge (SPG) or other breathing gas monitoring devices are essential pieces of equipment for scuba diving. As scuba divers, we can only stay underneath the surface of the water so long as we have an adequate supply of breathing gas; whether that be air, Nitrox or Trimix. Without knowing how much breathing gas you have remaining in your tank runs the risk of running out of gas which is one of the few diving emergencies which can be fatal. Running out of breathing gas is never an option for divers. You learn on your Open Water Diver Course to frequently monitor your gas supply, to end your dive and surface with at least 50 bar, or 700psi of pressure remaining in the tank.

A good diver never lets their tank become empty. Consequently, a device by which you can monitor your supply of breathing gas is standard and critical scuba diving equipment. In this blog, we’ll have a look at some of the ways divers monitored their supply of breathing gas historically as well as consider what some of the current products on the market are for keeping track of your gas supply. As always, there are hundreds of products out there so this is not exhaustive. If you have any questions about any piece of equipment you are diving with or thinking about buying, we are happy to help. You can send us a message, here.

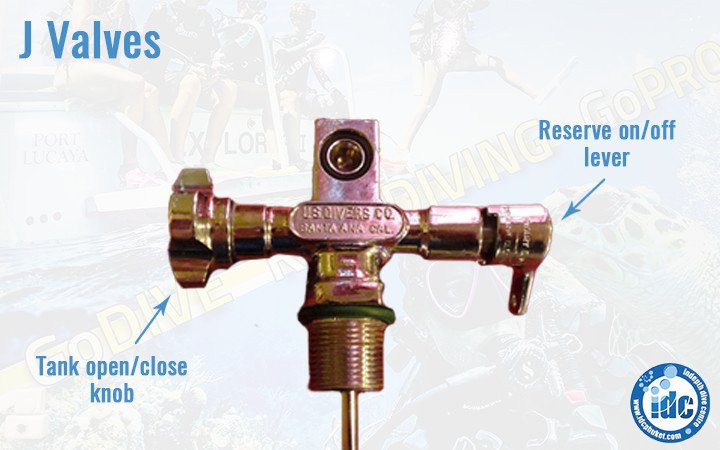

J Valves – Most basic Breathing Gas Monitoring Devices

Prior to the invention of reliable submersible pressure gauges in the 1970s, divers used to dive with what were known as “J” Valves, or reserve valves, fitted to their scuba tanks. A J Valve is a spring-loaded tank valve which closes the tank and cuts off the supply of breathing gas once the tank reaches 500psi or approximately 40 bar of gas remaining. This would serve as an abrupt warning to divers that their tank is nearing empty and that they need to end their dives. The diver could easily re-open the valve and re-establish the supply of breathing gas using a lever in which to do so. Up until the point of the J Valve activating, however, the diver had no means by which to monitor how much gas was remaining in their tank. You can find a good explanatory video about how J Valves work HERE.

J Valves are no longer common in recreational diving thanks to advancements in technology and equipment. They have been replaced by the submersible pressure gauge or SPG and dive computers which are a lot safer.

Submersible Pressure Gauge (SPG)

All divers these days use some form of SPG in order to monitor and read the remaining gas supply in their tank(s) throughout the dive. You learn the basics of gas management on your Open Water Diver Course and build on this understanding in your Deep Diver Specialty Course. In order to effectively plan your dives, you need to understand what your gas consumption is, how much gas you have in your tanks and at what tank pressure to turn, or end, the dive. If you can’t read what gas is remaining in your tank(s), you can’t properly plan or execute a safe dive.

Back-mounted tanks

Depending on where your tanks are mounted to you and how many tanks you are diving with; you may need different configurations of Submersible Pressure Gauge (SPG) to monitor the pressure in those tanks. The most important consideration when purchasing any SPG is that you are able to easily read them and there is at least one independent pressure gauge per tank. The only exception to this rule is for divers who are diving on back-mounted twin tanks, or a twin-set, which are connected by an isolation manifold. In this instance, one SPG is sufficient for both tanks as the manifold effectively connects both tanks and causes them to function as one single tank.

A standard SPG for back-mounted tank(s) attaches to the tank valve via the first stage regulator and connects to a high-pressure hose, long enough to reach around the diver’s left hip. On both a twin-set as well as a single, back-mounted tank, the standard hose length is between 61cm and 66cm. The SPG itself sits at the end of the hose, in a position where the diver is able to easily read it. Some buoyancy control devices have pockets to stow the SPG whilst others have D-rings for divers to clip the SPG hose to. The SPG should always be streamlined and never hang from the diver or drag on the bottom which can both damage the SPG itself as well as the environment.

Side-mounted cylinders, stage tanks, bail-out cylinders & pony bottles

Tanks which are attached to the side of the diver; whether they be sidemount tanks, decompression tanks, a bail-out cylinder used by rebreather divers or a pony bottle need a different configuration of SPG to back-mounted tanks. This is because the tank(s) and the valve(s) sit directly underneath the diver’s armpit(s), meaning the diver can easily see the tank(s) just by looking down. The diver also has clear access to all the tank valves on their sides. As such, the SPGs used on tanks attached to the side of the diver vary from those which are used for tanks on the back of the diver.

For side-mounted tanks, a long hose is unnecessary and cumbersome. Instead, a shorter Submersible Pressure Gauge SPG hose is more effective, streamlined and easy to read by the diver. Each tank must have its own pressure gauge and this also connects to the first-stage regulator via a high-pressure hose. The standard hose length for a side-mounted SPG is 15cm.

Some divers choose to do away with the hose altogether for their side-mounted tanks and instead fit a smaller SPG, known as a button gauge, directly onto the first stage regulator. This style of SPG physically screws into the first stage, in one of the high-pressure ports. It is very compact and small, however, can be difficult to read due to its size.

Both of these configurations of SPG are only suitable on side-mounted tanks and are entirely unsuitable for back-mounted tanks. The reason is simply that the has no way to see or read them when on backmount.

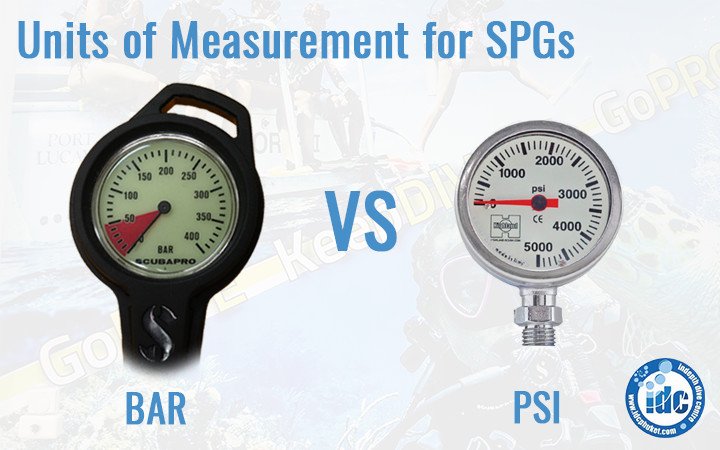

Units of Measurement – Submersible Pressure Gauge SPG

SPGs are available in both metric and imperial systems, reading pressure either in pounds per square inch (PSI) or bar. Depending on where you live and where you buy your SPG, they may only be available in one style. PSI is commonly used in America whilst bar is used throughout the rest of the world. Regardless of what unit of measurement you dive with, it is still worthwhile understanding both systems in case you dive with someone on a different system to yours, for example on holiday. A full tank holds a pressure of approximately 3000psi which is the equivalent of 207 bar. A tank is considered low on air once it reaches 50 bar or 700psi.

Analog vs Digital – Breathing Gas Monitoring Devices

Analog Submersible Pressure Gauges

SPGs connecting to the first stage via a high-pressure hose for both back-mounted and side-mounted tanks are usually analogue gauges. In simple terms, analogue gauges have a C-shaped, oil-filled tube inside of them. Once the tank is turned on and the hoses are pressurised, pressure fills the tube and causes it to flex. The SPG needle is attached to this tube and will move as the pressure increases or decreases. The face of the SPG itself is fitted with tempered glass so the position of the needle is easily read.

This style of SPG is very reliable, however, the face of the SPG can scratch if not taken care of. Over time and with wear, analogue SPGs can start to leak oil from the tube. If this occurs, the SPG needs to be replaced. The most common sign of wear for an analogue SPG is from the O-ring where it attaches to the hose. If small bubbles are visible from the hose, the SPG needs servicing. As a general rule, SPGs should undergo servicing on an annual basis, along with first and second stage regulators.

Digital Submersible Pressure Gauges

Many divers are now opting to use digital SPGs instead of the analogue gauges. A digital SPG connects to the tank in the same way as an analogue SPG does, via a high-pressure hose and for back-mounted tanks, long enough to reach around to the diver’s left hip. A digital SPG is effectively a computer and uses a different mechanism to detect the tank pressure compared to an analogue gauge.

The advantage of a digital gauge is accuracy. A digital gauge shows how much remaining gas you have in your tank down to the single bar or psi. Analogue gauges on the other hand have markings at 10 bar increments which reduce the accuracy of readings. Analogue gauges, however, are less prone to failure and don’t rely on batteries to operate. As a digital gauge is electronic, it can also be affected or compromised if exposed to strong magnetic fields. Generally, digital SPGs are more expensive than their analogue counterparts.

Computer integrated transmitters

Another breathing gas monitoring device option for divers is a wireless transmitter communicating directly between their tank and dive computer. This will remove the need to use any hoses at all. The transmitter screws into a high-pressure port on the first stage regulator, and connects to the dive computer via Bluetooth.

Advantages

The advantage of having a transmitter communicating with your dive computer is that you only need to look in a single place to get all the information you need on the dive. Everyone else has to look at both their dive computers and their Submersible Pressure Gauge SPGs throughout the dive. As the computer is digital, it is reading the pressure to the exact bar, or psi and is much more accurate than an analogue SPG which measures the pressure in ten bar increments. Some computers will assess your breathing rate against the remaining gas and even tell you what your surface air consumption rate is and how much longer you have left to dive if you stay at that rate.

Disadvantages

One of the downsides of a wireless transmitter is that the data connection & transmission can be lost or interrupted. If the diver is unable to re-establish the connection, this may result in the dive being prematurely ended.

Another problem with wireless transmitters and single dive computers is that they become impractical when diving with multiple tanks. The manufacturer Shearwater has gone some way to addressing this issue by producing a pair of different coloured transmitters. Each will attach to a different tank, and read separate tank pressures, but connect to the single Shearwater computer. Unsurprisingly, this capability is more expensive than that of a single tank transmitter and computer combination.

A downside of using transmitters is that they can be bumped or damaged as they protrude from the first stage. Some of them can also be temperamental and difficult to pair with the dive computer; particularly when there’s interference from more than the one transmitter, transmitting on the boat.

Battery life

This system also relies on the transmitter itself having sufficient battery. Depending on the manufacturer, the battery life of the transmitter varies. The Suunto transmitter, for example, can last up to 100 dives or approximately 2 years. The dive computer also needs to have sufficient battery in order to communicate with the transmitter. Not all models of computer and transmitter allow their users to replace their batteries by themselves. They often need to be returned to the dive shop and then pressure-tested by an authorised technician.

For the reasons above, many divers still keep a standard analogue SPG as a back-up device to their wireless transmitters.

Night and limited visibility – Submersible Pressure Gauge SPG

All SPGs and breathing gas monitoring devices, be it analogue, digital or wireless, need to be readable in all conditions. Most analogue SPGs will glow in the dark after exposure to sunlight or a torch for a few seconds. This allows the diver to read them on a night dive or in low light situations. Digital SPGs and computers often feature lights which the diver can turn on to illuminate the screen. Other computer types like Suunto EonCore have lights constantly on, allowing to easily read the display in any light conditions.

We recommend you come in and have a look at as many different types of gauges and computers as possible. This is the best way to find the right one for you and the type of diving you plan doing. If you have any questions about any piece of equipment or would like to arrange to do some dives with us, please contact us here.

More posts about diving equipment:

- Choosing Dive Equipment

- Choosing a Scuba Diving Mask

- All about snorkels

- Choosing the right fins

- Scuba Cylinders & Valves

- Buoyancy Control Devices (BCDs)

- How to choose a Scuba Regulator

- Depth Monitoring Devices

- Scuba Diving Weights & Quick Release Weight Systems

- Choosing a wetsuit for Scuba Diving

- Audible Signaling Devices for Scuba Diving

- Choosing a Scuba Diving Compass

Credits: J Valve photo – Joseph G. Bergstrom, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons